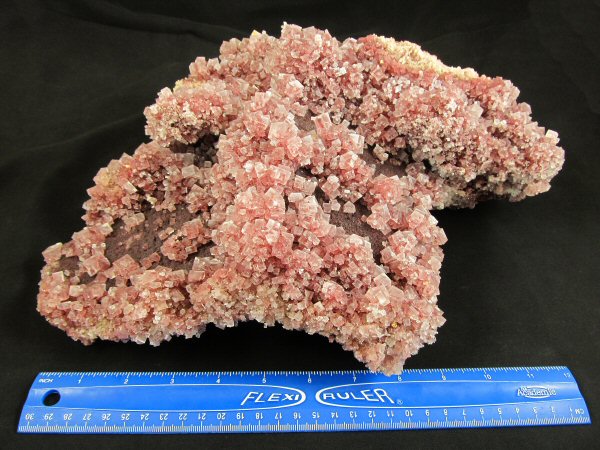

If you’ve read my earlier blogs, then you know that I make an annual trip to Trona, California, for the Searles Valley Gem and Mineral Society Show, and to go out on the Searles Lake field trips, to collect world class evaporite minerals, such as this marvelously textural, large pink halite.

One of the great rockhounding sites I pass by, on my way south, down Hwy 395, is Peterson Mountain, also known as Hallelujah. Here the road to Peterson invites me to drive on in and get a little digging done, with the peak directly ahead, and flaring orange in the last light of the setting sun. Believe me, I definitely think about it!

Anywhere you dig has potential for smoky quartz crystals, but there are two claims up on the very top of the mountain, where permission is needed. In this picture, you can see the slide zone which extends on either side of the main rampart of rock near the summit. Crystals have definitely come from this area, and also from the sage slopes to the either side.

How do you know when you’re there? Peterson Mountain is about 70 miles south of Susanville, CA, and 30 miles north of Reno, NV. It is accessed by an unmarked dirt road, spurring off of Hwy 395, that is exactly one mile south of the road signed “Red Rock Road”. You will see Red Rock Road as you are traveling south on 395. If you are heading north on 395, you will see these red rock formations, and know that you are very close.

Here are some of my best finds from nearly 20 years of rockhounding on Peterson Mountain. It strikes lightning into your heart when you find something like this! But remember, large scepters are rare. Realistically, you would probably need to make repeated trips over many years to hit a pocket that would yield a specimen like this. But then again, I’ve seen some first-timers that were handsomely rewarded by the mountain. Are you feeling lucky?

An ancient earthen union, brought to light.

Huge elestial scepter, with smaller (but still good sized) scepter keyed into it.

Here’s the other side of this beauty!

How about this otherworldly design? The main stem crystal actually is terminated, although it’s hard to tell from this angle. An almost ridiculous, yet entirely awesome amethyst and citrine elestial scepter head is partially wrapped around the large central smoky.

Who would have believed that such a geometry is possible?

A burly “turkeyhead”, as diggers call these large elestials.

Smoky amethyst tips!

Back on Hwy 395 and heading to Trona, I pass through the scenic Walker River Valley, on the east side of the Sierras, south of Topaz Lake. Snows have been coming early to this part of the country, and you can see the hill on the horizon is dusted.

As the highway climbs higher, over on the back side of Yosemite, geothermal features are plainly revealed in the cold snap.

Just before I get to Mono Lake and around 7000 feet, I come to my favorite forever view of the high Sierras. Quaking aspens are turning gold, and running up and down just about every draw, as the land does a slow, undulation up towards the cloud capped summits.

Aspens turn to flame beneath the silence of the frozen peaks.

Just around the corner, Mono Lake glitters enchantingly in the sullen light. The lake has been pulled back from the brink of destruction since a 1994 ruling mandating that water levels be restored to a higher mark, though still 25 feet below historic levels. Years of water diversion have brought a loss of 98% of the migrating duck population that once visited. The future now seems to hang in balance, like the scene over the lake this morning, with the fullness of the silvery light still shrouded by the circling storm.

I drop down from the snow zone, closer to the shore of Mono Lake, and can’t resist taking a walk among the Quakies. Their golden bounty is fluttering down to earth, and covering the hillsides.

Creamy boulders of granite, smoothed by the weathering of eons are everywhere on the back side of the Sierras. To the stones, the brief pagentry of the trees must appear as only some quick flame that exhausts itself before one can turn and behold it.

I make it to the desert! There’s some daylight left, so I decide to explore the mine grouping around the Talc Hills, accessed out of Lone Pine, via Hwy 190, just before it drops into Panamint Valley. The Talc City Mine produced nearly all the steatite grade talc in the US. By 1950, it’s total production was a quarter of a million tons.

A ramshackle talc ore chute falls apart at the top end of a cut.

A logo is still visible on one of the metal sheets.

There is a little druzy botryoidal chalcedony around here, but not much.

The miners’ last ride. A rusted hulk sits down in the bottom of a talc pit.

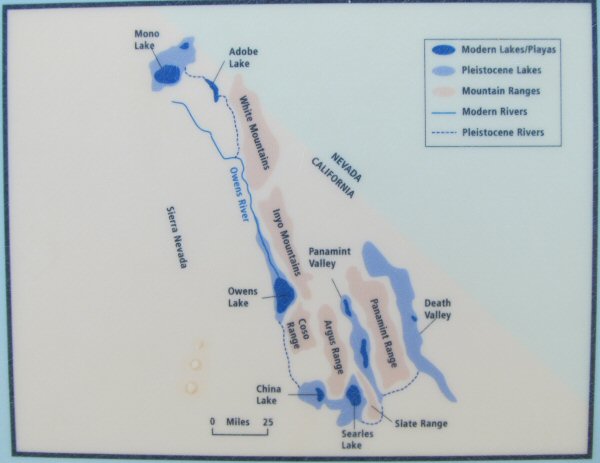

The next morning, I catch the dawn at the Trona Pinnacles just south of Searles Lake. The murky hold of night is slowly washed away by the oncoming light. These ancient tufa towers are composed of calcium carbonate, deposited by calcium rich groundwater mixing with alkaline lake water during the Pleistocene Ice Ages.

During this time, massive runoff spilled from the Sierra Nevada, creating a chain of “inland seas” – a system of interconnected lakes that stretched from Mono Lake, to Death Valley, and included Searles Lake.

The silent monoliths from a bygone time stand witness as the muted tones of the night are thrown off in a golden sunrise.

Markers of ancient groundwater upwelling episodes that spanned 90,000 years, the ragged spines of pinnacles run out into the emptiness of the new day. The steam from the Searles Valley Chemicals processing plant is barely visible at the top left of the picture.

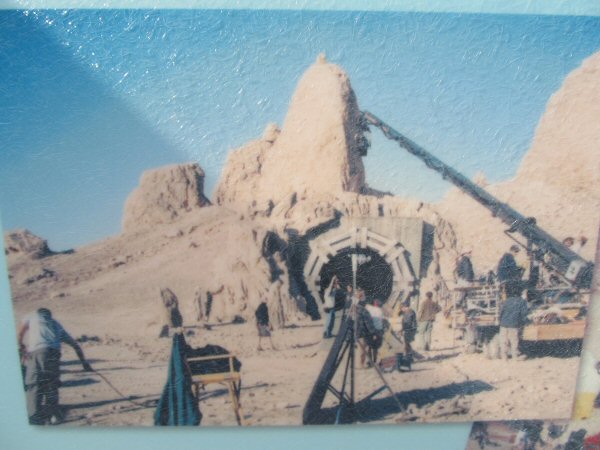

Interestingly, I learn from an interpretive sign that over 30 film projects a year are shot here at the Trona Pinnacles, including movies like Star Trek V, The Gate II, and Planet of the Apes.

Let the gem show begin! Bonnie Fairchild, shown here staffing the show office, along with her husband Jim have been the show anchors for decades. Without them, and a small number of volunteers from the club’s membership, there would be no show and field trips!

Outside the show building, Jim Fairchild gives instructions to hundreds of eager field collectors, who are lining up for their once a year opportunity to collect some excellent pink halite. Check some of my other Trona blogs to get more details of this very significant weekend of field tripping.

Another pillar of the Searles Valley Gem Show, resident and miner Gail Austin cuts hundreds of geodes for attendees at the show. Here he shows off his 1873 first generation Peacemaker, made by Colt.

It’s “the gun that won the West”, and has been fully, and painstakingly restored by the same person who does antique gun restoration for the Smithsonian.

Additionally, I’m hanging out with rockhound Monica Travis, who is showing off an excellent boulder of Ballarat marble that she has found, just south of the ghost town of Ballarat, in Panamint Valley. The beautiful salmon colored marble with forest green streaking takes a very nice polish.

This rock has about as nice a patterning as I’ve ever seen.

We are joined by University of Texas at El Paso geology graduate students Jade Brush, and Josh Glauch who are doing some masters work in the area, re-mapping geological units in Pleasant Canyon, over in adjoining Panamint Valley. As Jade put it, “When I looked at the existing geological map of Pleasant Canyon, the units just didn’t make sense.”

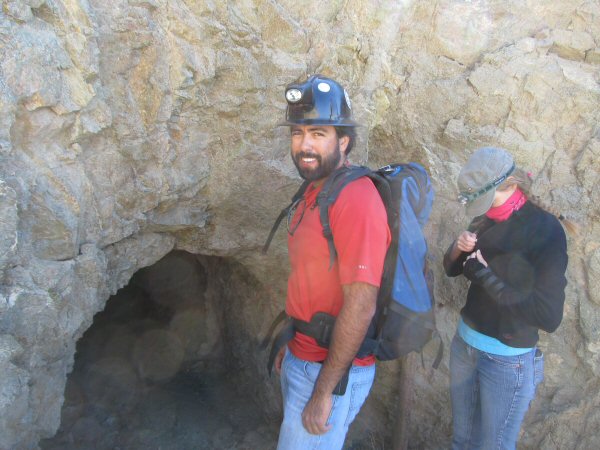

We all set out on a field trip to the Stockwell Mine, on the flanks of the Slate Range, east of Searles Lake, where it was reported that a couple of sheriff’s deputies, who are also rockhounds, made a find of chalcanthite earlier in the year. Soon after this photo, the road gets washed out and not even Josh’s 4×4 can proceed.

We move up into the canyons on foot. Josh is a strong hiker, and he is able to access multiple ridges, looking for the mine. Jade tries to recollect the exact location from memory, as she was here years before, but at that time, you could drive right up to the mine.

Like many mines in this part of the country, the Stockwell Mine is actually a mine grouping. We are looking for a specific tunnel, but there are numerous adits and shafts in various canyons in the area. Josh and I get distracted by an old can dump at the bottom of an ore landing.

In a neighboring canyon, Jade has confirmed that this is the tunnel she visited earlier, and where the chancanthite was reported. It’s showtime at the Stockwell!

Before we go in, my disclaimer: Exploring a mine tunnel is inherantly dangerous. In posting this blog, it is the sole intent of Scott’s Rock & Gem to provide a record of exploration, and not to encourage anyone to enter a mine. To do so is to enter at your own risk. In fact, the common wisdom among rockhounds who operate safely, is to stay out of all mine tunnels! We have it on the authority of the two sheriff’s deputies who explored this tunnel and located the chalcanthite, that it was safe. Also our miner friend, and Trona local, Gail Austin has said that it is a good tunnel. But as we make the decision to go in, each of us knows in the back of our heads that anything can happen.

We head in, and the light of day drops away behind us. The air deadens and grows stale. Large piles of rodent dung lie drifted here and there, and we try not to think about the dreaded hantavirus. Or falling rock. Up ahead, the tunnel tees and we make a right, into complete blackness.

A ladder descends into a vertical shaft that is just big enough to admit one person. Josh goes for it. Again, we had the assurance from miner Gail that the timber in this mine would be good. He based that on his knowledge that the mine had been worked as recently as 1975, and his experience of how well wood holds up over time in mines in this arid land. But as each of us takes hold of the top rung and we begin to lower ourselves into uncertain darkness, there is no doubt in our minds, that this is getting more dangerous by the minute.

The ladder holds and we drop down into a lower tunnel, which quickly confronts us with another ladder. Still no chalcanthite in sight. We start to doubt ourselves because the deputies had only mentioned one ladder. Did we miss something somehow? Did we get off track? Josh forges ahead, determined. But the second ladder drops us onto a makeshift plank scaffolding that traverses a vertical shaft of unknown depth. Without a doubt, things are getting a bit hairy.

Here, Monica descends a third ladder, and navigates a missing rung, while Jade spots. Josh has already continued across more funky planking, and has discovered a fourth ladder. I’m starting to think that we must have missed it. But just then, Josh calls up: “Chalcanthite!”

The Stockwell chalcanthite zone exists as a secondary mineralization after mining, in a very fractured seam of white clay. It’s quite rich with nice, fibrous blue crystals of chalcanthite filling in between the fractures in the clay. But there are some large lumps of fractured clay up at ceiling level that look like they may want to come down. Hopefully, not on anybody’s head. Believe you me, I am looking up at that ceiling frequently, as I gingerly pull a few samples from the crumbling wall. But there is a good amount of chalcanthite, and no rocks fall. Everybody gets some nice samples.

I think we all breathe a sigh of relief as we round the last corner on our exit, and see the heavenly light of day.

Back outside, Josh shows off an awesome, large chunk of clay just chock full of brilliant blue chalcanthite sprays. We work quickly to seal the mineral specimens with a clear coat of varnish. This is because chalcanthite is a pentahydrate. Having five waters in each molecule, it wants to give off water and dessicate very quickly. It must be sealed and protected from direct sunlight, and heat.

Here’s a great piece, with large area of undamaged, bright blue fibers.

Another very nice specimen with good coverage.

A superb, larger than hand-sized specimen with feathery tufts exploding across the surface.

How about this blue? Just to cure any skepticism: no photoshopping of any sort has been done to this photo! If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading. As always, I wish you good times in the field, good memories, and good luck in your collecting!